Acesso Rápido

Jornalismo

Temas

Formatos

Programas

Conteúdos

Apoia o Gerador na construção de uma sociedade mais criativa, crítica e participativa. Descobre aqui como.

The discovery of and dispute over natural resources has been the setting for great historical reenactments, often altering the course of history itself, Bill Laws1 states in Fifty Plants that Changed the Course of History.

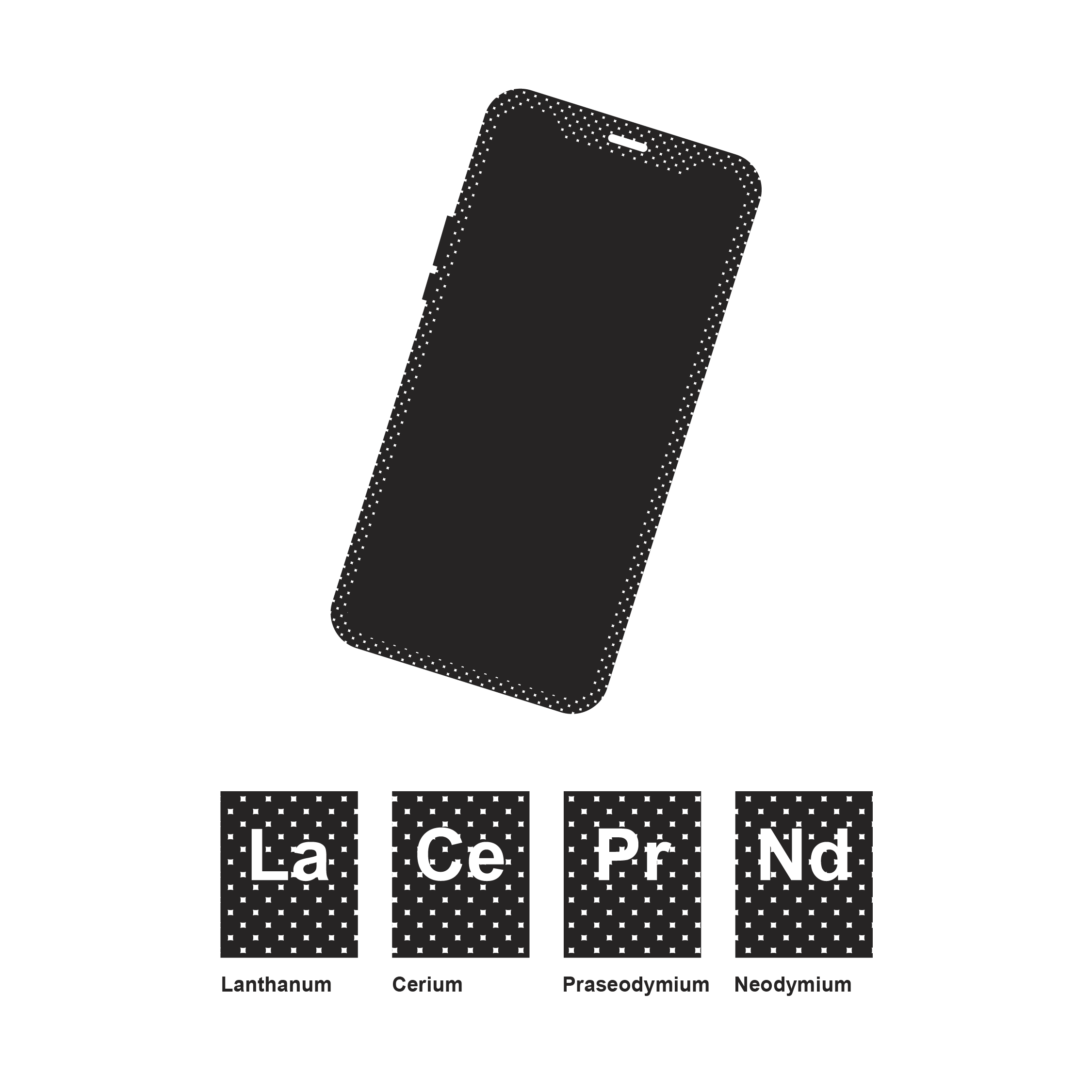

As a matter of fact, mineral raw materials do have the power to affect international cooperation by creating geopolitical tensions or intergovernmental alliances, to be implicated in major controversies linked to human rights abuses and the perpetuation of crimes against humanity. Yet they can be so intricately embedded in our everyday lives, in our objects of daily use, such as a mobile phone or computer, that they pose tremendous decisions on the course of humanity, in the daily choices of citizens. Choices so discreet that they fit in the pocket of a pair of trousers or a coat without us even being aware of it.

The last and fourth industrial revolution, commonly known as the Green Revolution, arose from the need to decarbonize the economy and energy, creating more efficient and cleaner energy systems and avoiding the deepening of the current climate crisis. Carlos Santos Silva, a researcher and scholar at the IN+ of Lisbon’s Instituto Superior Técnico, also stresses that Portugal is “one of the most vulnerable areas to climate change in Europe”.

In 2015, the “first universal agreement in history,” the Paris Agreement, was concluded by 195 countries that committed to limiting global warming, keeping it below 2 °C and, ideally, 1.5 °C, compared to pre-industrial levels, a commitment that was reinforced at COP262 in 2021.

In order to materialize the efforts necessary to meet the established global goals, the European Union proposed a roadmap – the European Green Deal (EGD) – outlining a pathway for Europe to move towards a sustainable future “Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent”, the priority being to achieve zero net emissions of greenhouse gases by 20503.

Among the several areas covered by the EGD, the Energy and Digital Transition has been presented as the panacea for the current climate crisis, and is currently the “very engine of Europe’s economic development”, according to Carlos Santos Silva.

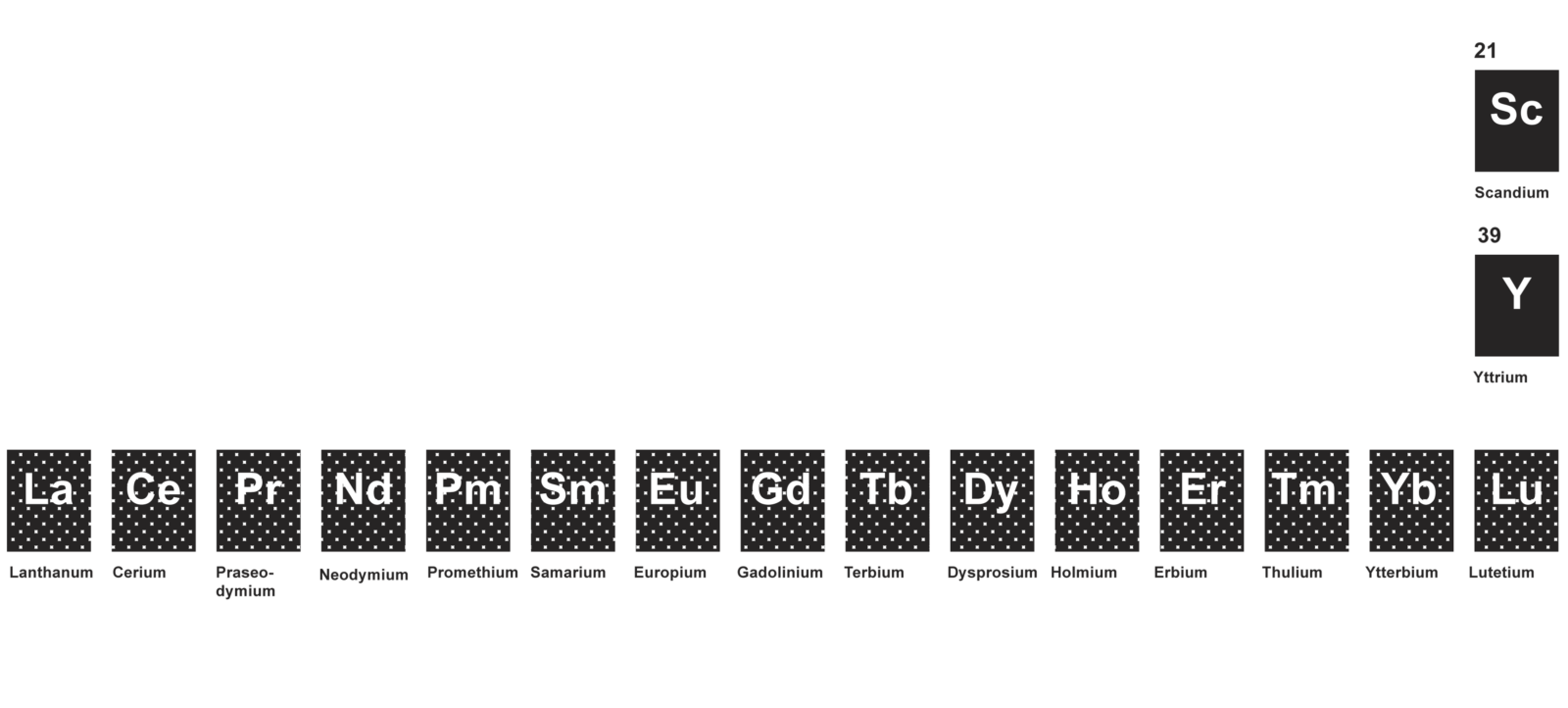

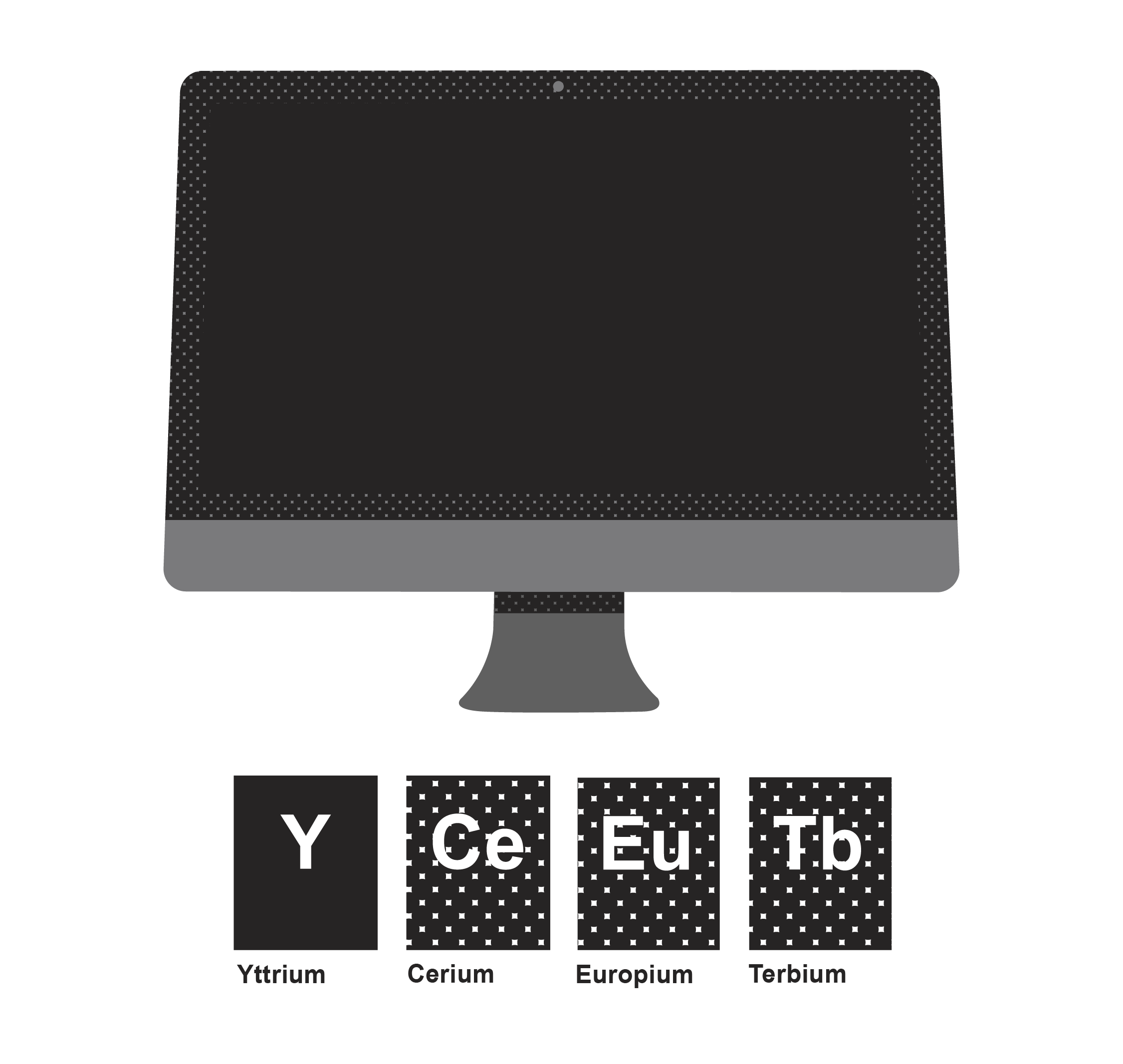

As with previous industrial revolutions, this one also requires raw materials to fuel the energy and digital transition, which are a set of 30 ores called rare metals. Within the set of rare metals, rare earth metals are currently the most highly prioritized of all critical raw materials (CRM)6 for European economies and the green policy agenda, according to ERMA (European Raw Materials Alliance).

“That is a problem that both we scientists and also industries know very well: we are extremely dependent on metals,” says Ana-Maria Martinez, senior research scientist and the project coordinator of REE4EU (Rare Earth Recycling For Europe) and partner in the SecREEts (Securing European Rare Earth Elements) project.

Guillaume Pitron, a French journalist and documentary filmmaker, author of the book The Rare Metals War, states that “Green energies and resources harbor a dark secret”, referring to the paradoxes and negative externalities inherent to the current Green Revolution.

In fact, although in their lifetime renewable energies do not negatively impact the environment, since they do not release greenhouse gases, the production of the technology needed to generate renewable energy combines a series of extremely polluting processes, including the need to extract huge quantities of rare metals.

Chinese environmental activist Ma Jun stresses that “it is no longer enough to look at the green and non-polluting end products”, stating that we must also confirm that the manufacturing process of these technologies is sustainable in terms of its social and environmental impact.

According to the US Geological Survey and the European Commission, China is the largest producer of most of the world’s rare metals, and especially of the supreme “green” metals, whose intrinsic properties surpass, in performance and worldwide recognition, all others: rare earths.

Rare earths are metals grouped into a set of 17 chemical elements of the periodic table. It is their relevance in the magnetic process that makes these minerals essential for renewable energies, making it possible to create high-performance electric motors. A small dose of rare earths releases a magnetic field capable of generating more energy than the same amount of oil or coal (in The Rare Metals War).

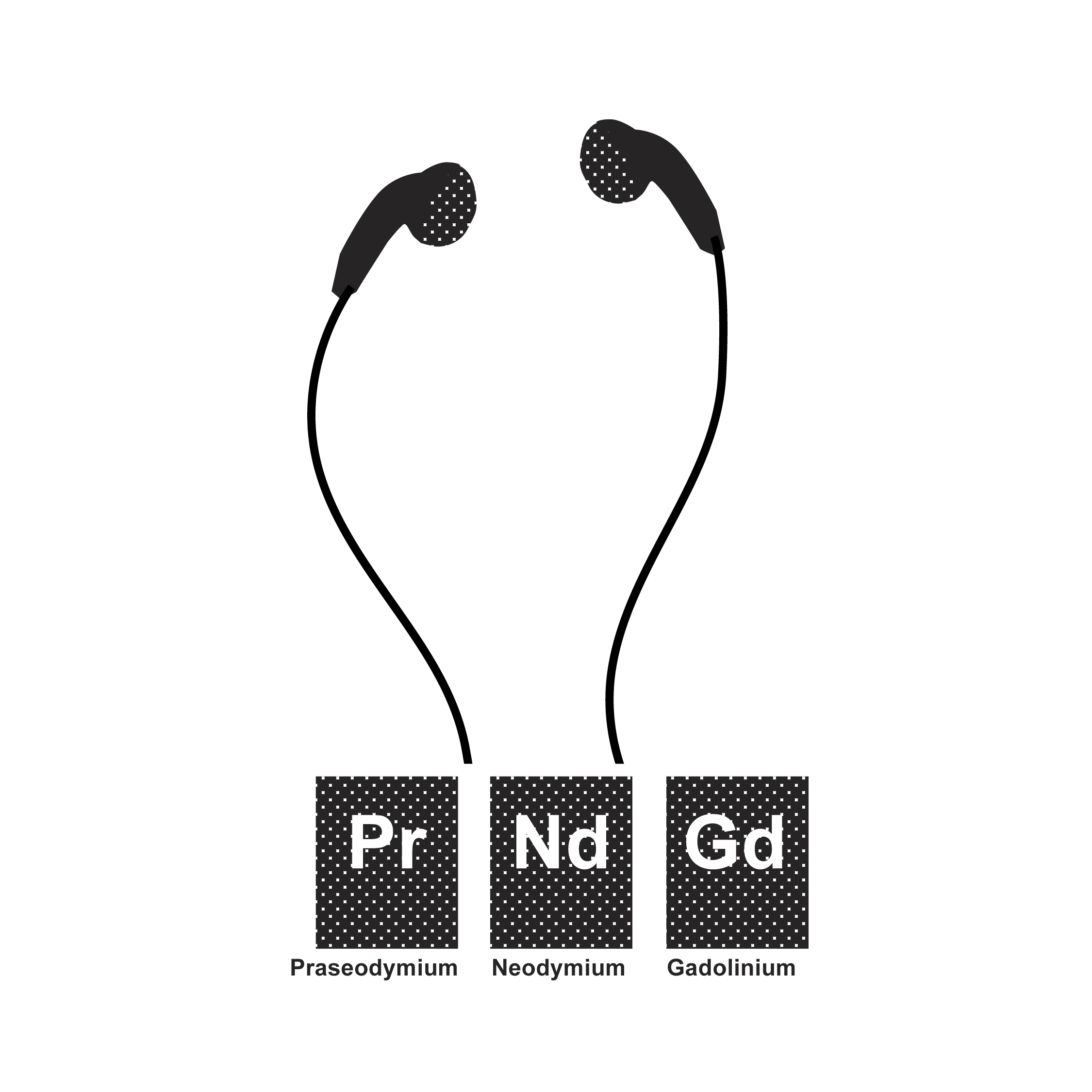

Rare earths have electromagnetic, electronic, catalytic, optical and chemical properties that are vital to a range of industries, such as electronics, military and renewable energy, as they are used in the production of green technologies such as wind turbines and electric vehicles (according to National Geographic Portugal, March 2022). They are also deeply embedded in our daily lives, making up the components of our mobile phones that allow them to vibrate, the constituent parts of the hard disks in our computers, and vital elements in our earphones.

New uses for these metals are found every day, and their exploitation has gone beyond the limits of the earth and into the ocean – several countries have in consequence requested the extension of their exclusive economic zones7.

Overseas, the race to extract rare earths was also redirected towards space, when in 2015, the former US president Barack Obama signed the “Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness”, which guarantees any American citizen the right to own, transport, use or sell any resource from space. Despite still being a distant and, for the moment, utopian reality, the idea of commercial space mining and exploration has become a possibility.

In fact, Hollywood has also covered this new “gold rush”, in the satirical film Don’t Look Up, based on the asteroid 2011 UW-158, also called Trillion-Dollar Asteroid, which went by near Earth in 2015, attracting the gaze of several NASA scientists. The value of its composition, 90 million tons of rare metals, is estimated at 5000 billion euros.

In 1992, former Chinese President Deng Xiaoping, a forerunner of China’s current economic reform and development, said: “The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths”, referring to the power that these elements would come to have as the “gold of the 21st century”.

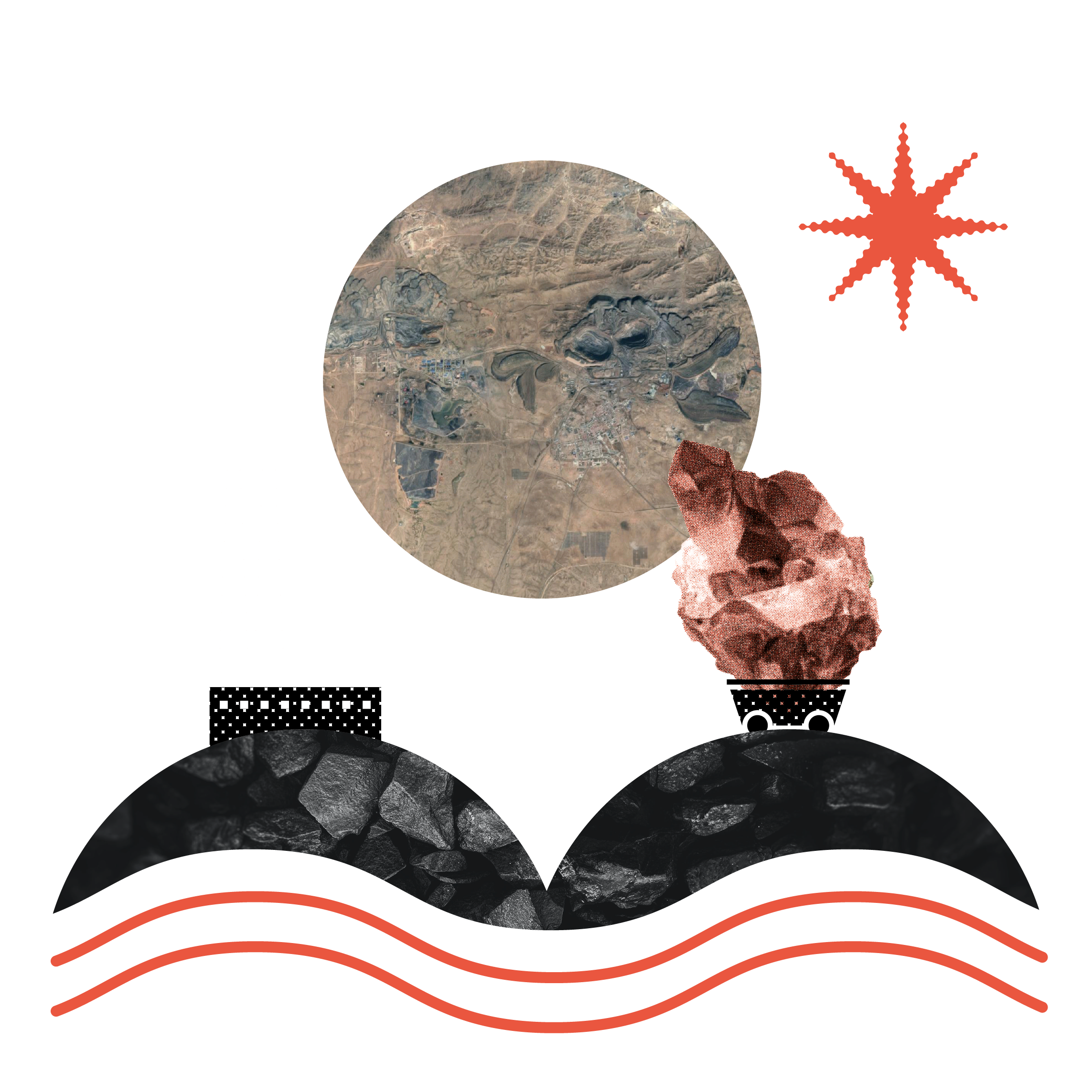

Contrary to what the current paradigm seems to dictate, the largest reserves of rare earths are not found in the most active operational mines, such as China’s, but are actually scattered across the planet in different concentrations8.

In fact, from 1952 to 1980, the largest operational rare earth mine was located in the United States, at Mountain Pass in California, and France owned a chemical company in La Rochelle that purified 50% of the planet’s rare earths.

The adverse environmental effects of rare earths exploitation started to be unbearable for local populations, who, through public pressure on local governments, secured stricter environmental regulations which forced investment in modernizing facilities, making processes more expensive and therefore less profitable (according to the report “Rare Earth Mining At Mountain Pass”, Desert Report, March 2011).

In the face of less stringent environmental and labor legislation and standards in China, allowing for lower cost production, both the US and France decided to abandon their position as world leaders in the rare earths industry in the 2000s, and relocate it to China, thus benefiting from more competitive prices and avoiding the direct environmental consequences inherent to rare earths mining, as Guillaume Pitron explains in The Rare Metals War.

China, on the other hand, has managed to position itself strategically on the energy issue, and has now become the main, and sometimes only, supplier of the most strategic rare metals for the energy and digital transition, as is the case with rare earths.

“China controls us. China knows that if they control the supply of mineral raw materials, they control the market,” Ana-Maria Martinez says.

The Chinese strategy, combined with that of the West, has allowed China to control 90% of the entire value chain of rare earth magnets, and 98% of the supply of rare earths to the European Union, according to European Commission data9.

Today, China holds not only the global monopoly on the supply of rare earths, but the technological expertise and know-how [experience and knowledge] needed to produce the most sophisticated technologies crucial to the energy transition [according to the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)’s 2018 study and report, “Green Conflict Minerals”).

According to the report “Rare Earth Magnets and Motors: A European Call for Action”, the Chinese Central Government owns most of the companies within the rare earths sector, which gives it control over the supply of these metals, thus leading to distortions on the market price of rare earths.

The document also adds that in December 2021, China applied the “Export Control Law,” which involves the application of export duties and consequently quotas that limit the export of rare earths to the rest of the world.

This intervention in the international rare earths market has generated complaints10 to the World Trade Organization from the US, the European Union and Japan, all accusing China of violating international trade laws by distorting prices.

Furthermore, the non-disclosure of information by the Chinese Government reveals, according to the European Call for Action report, lack of transparency regarding standards and the social and environmental impact of the rare earths value chain, as well as regarding levels of governance of these resources, making the rare earths market opaque and poorly regulated.

The global dependence on China, throughout the rare earths value chain, has affected the harmony of international cooperation and the security of sustainability of European economies, creating geopolitical tensions, with China’s use of the rare earths’ monopoly as a commercial weapon against the rest of the world, in order to reassert its political power, as has already happened in several episodes since 2010.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), this insecurity in the supply of rare earths will be accentuated by the growing global demand for them. It is estimated that in order to achieve the European target of zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, the demand for rare earths will be six times greater than at present in 2040.

For the European Union, the political impact of regaining control over the rare earths’ value chain is a priority, for several factors, but particularly because this dependency “limits our ability as a political region to exercise our voice in other matters”, Carlos Santos Silva states.

Rare earth extraction and refining processes are immensely damaging to the environment, as they produce high levels of toxic waste with major risks of radioactivity. The refining of one metric ton of rare earths produces 2000 metric tons of untreated toxic waste (The Guardian, 2014).

In China, rare earths tend to be mined in rural areas, and the main areas responsible for the largest percentage of rare earths mining and export are the cities of Ganzhou in Jiangxi province and Baotou, in Inner Mongolia, which is responsible for extracting 75 % of the rare earths exported to the rest of the world, according to the South China Morning Post (The Guardian, 2014).

According to testimonies collected in The Rare Metals War, the residents of Jiangxi province claim that the earth is poisoned, as the chemicals used in the refining of rare earths seep into the earth, and sulfuric and hydrochloric acids pollute nearby water sources, making it impossible for any plant to thrive.

However, Jiangxi’s situation does not compare with Baotou’s.

The entrance to Baotou city parks, is covered with posters depicting the “happy family”, parents and children against a green and pristine background, with the title “Building a clean city for our country” – the perfect postcard of a dystopian reality11

The mines in Bayan Obo, located 120 km from Baotou’s city center, are among the most polluted areas on the planet, and are also the heart of the world’s energy and digital transition.

The environmental destruction caused by the rare earths industry not only takes the form of toxic pollution levels, but also disfigures the landscape: in Baotou, a city set at the foot of the Yin Mountains, on the northern side of the magnificent Yellow River, where 65 years ago there used to be green landscapes until the horizon was lost and clear, invigorating air, a place with spiritual significance for the Mongolian population, there are now 3000 companies and factories, according to China Daily, as well as the world’s largest open-pit rare earth mine, which is 48 km2 long and 1000 meters deep, and has mines covered with thick streams of toxic air – considered one of China’s biggest environmental disasters by several Chinese environmentalists (The Guardian, 2014).

Twenty kilometers from the center of Baotou there is also the Weikuang Dam, an 11.5 km2 artificial lake that churn out torrents of thick, black water emitting toxic, unbreathable air, into which metal and toxic tailings from surrounding refineries, particularly those of rare earths, are dumped. According to the Environmental Justice Atlas (EJA)’s report12 on Bayan Obo, the Yellow River, which provides drinking water to 155 million people, is occasionally flooded by the toxic tributaries of the dam, which contains 150 million tons of tailings.

The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention concluded in 2004 that thorium tailings (a radioactive metal) have been linked to increased cancer and mortality rates among rare earth mine workers.

This is true in the villages surrounding the artificial lake, named “Cancer Villages,” such as Dalahai, designated as the “Death Village” due to the exorbitant rates of brain tumors, lung cancer, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases among local residents, according to the article “Protecting the Environment and Public Health from Rare Earth Mining” (2016). According to the same article, Dalahai presents a thorium concentration in the soil 36 times greater than that of the city of Baotou, which means that the inhabitants of these villages breathe, drink and eat the toxic and radioactive discharge from the lake, which gets into the soils and, consequently, into the groundwater, thus contaminating everything it touches. The land is no longer suitable for growing local crops, and the few cattle that are born have serious deformities, and most have died off little by little13.

Meanwhile, illegal mines are a major contributor to pollution levels in China, as they even eschew the few existing environmental and social-labor regulations, which allow them to fall into a sort of “gray area” where their actions go unnoticed under a curtain of lack of legislation and control, according to local activists in Guangdong province14.

Over the past few years, the Chinese Central Government has been making concentrated efforts towards the banning of illegal activities linked to the rare earth industry, such as illegal mines where rare earth elements are extracted, the Los Angeles Times noted in 2019.

However, these efforts have been thwarted by the owners of the illegal mines, who maintain the secrecy of the deal with the support of local authorities who police the extraction areas in exchange for a payout15

The illegal mining of rare earths feeds the Chinese black market for these minerals, allowing the origin of the minerals to be laundered in the value chain, and making it difficult to trace them, and thus to understand the conditions of their extraction and processing once they are exported abroad, as they enter the international legal market. It is estimated that the black market for rare earths makes up 1/3 of the official supply of rare earths in China16.

Julian Hilton, the chair for the Sustainable Development Goals Delivery Working Group of UNECE17 and a consultant at the IAEA18, argues that we are experiencing a period of profound paradox: “we want all the benefits; we want security of supply, access and affordability; what we don’t like is the means of production and the consequences that come with it.”

In fact, according to Statista19 data for 2021, Europe is the world’s largest per capita producer of electronic waste, and electronic waste is a secondary source rich in rare earths (according to The Urban Mine platform).

Despite this, according to the scientific article “Electronic Waste, an Environmental Problem Exported to Developing Countries: The GOOD, the BAD and the UGLY” (2021), less than 1% of rare earths are recycled in Europe and the European Union estimates that 50% of its total e-waste20 (about 1. 5 million tons21), from which rare earths could be recovered to minimize Europe’s dependence on China and ensure security of supply, is illegally exported to developing countries22 such as Ghana, home to the world’s largest and most polluting dump of electronic waste, and Nigeria.

Amir Lebdioui, lecturer in Political Economy of Development at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, says that in order to truly assess the European Union’s environmental performance, it is necessary to conduct a life-cycle analysis23, including the indirect greenhouse gas emissions of European value chains that arise from the consumption of imported products. According to this analysis, there is an 11% increase in CO2 emissions from all member states compared to the analysis of direct emissions, as stated in the 2017 article “Europe’s Carbon Loophole”.

However, Clara Boissenin, the coordinator of project SecREEts in the area of social acceptance in the rare earths sector, explains that such a life cycle analysis of EU-funded projects poses a big problem for them, due to the lack of information on China, which “is not available or else it is very well hidden.”

“We are facing major challenges in the environmental field, and we have extremely demanding targets just around the corner. New technologies require minerals. And where do these minerals come from? From mining. And what is mining? It’s dirty [an industry]. I don’t want it in my backyard”, reflects Ana-Maria Martinez about the common European mentality.

The scientist and researcher explains that this trend has led to a halt to mining in Europe in the last 50 to 60 years.

“I don’t think China is to blame. It’s our fault”, Ana-Maria Martinez reflects, regarding Europe’s dependence on China and the current state of the rare earths’ value chain in terms of its environmental impact. So does Julian Hilton: “The West has a habit of blaming others for problems it has created itself”, rare earths being one such case.

The lack of transparency and trust in the data provided by the Chinese government about its environmental performance has proven to be a problem for the international community, since the Chinese Central Government blocks the information to the outside, concealing the Chinese reality. The same happens at the civil society level. The Chinese government’s repression of human rights defenders, journalists and activists, as well as restrictions on information and media access, make it difficult to get accurate information about the government’s policies and actions, the Human Rights Watch stated in 2020.

The lack of transparency and trust in the data provided by the Chinese government about its environmental performance has proven to be a problem for the international community, since the Chinese Central Government blocks the information to the outside, concealing the Chinese reality. The same happens at the civil society level. The Chinese government’s repression of human rights defenders, journalists and activists, as well as restrictions on information and media access, make it difficult to get accurate information about the government’s policies and actions, the Human Rights Watch stated in 2020.

Environmental protests against state-owned rare earth companies and criticism of the government are met with repression, including prison sentences of protesters on the pretext of “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in 2019 while covering the protests in Guangxi province.

Given the inaccessibility of public and official information on environmental strikes and climate activists’ actions in China in recent years, we consulted the Fridays For Future movement24 in order to seek data that would describe the current paradigm of climate action in China.

Consulting the movement’s map, we can see that China has recorded 24 strikes since 2019 (to the date of the last consultation for the purposes of this research: March 8, 2022), while on the same dates Europe recorded 12 374 strikes. The discrepancies are striking, especially given the size and population density of China, which holds a population of 1402 billion, according to the World Bank in 2020, compared to the European Union’s total population of 447.2 million, according to Eurostat in 2020.

Within the 24 strikes that occurred in China, 11 took place in locations where rare earths are mined25. Of those 11 strikes, five occurred in the same city, Guilin in Guangxi province, the only location with any information on the report associated with the strike.

Among the information available in that report, there was only one tweet. It was that tweet that led us to the person behind those five strikes. The media calls her the “Greta Thunberg of China” and her name is Howey Ou26.

It didn’t take much for Howey Ou to make herself available to talk to us. The desire to change the paradigm of climate action in China has been the driving force that led the young woman, who was 16 at the time, to single-handedly protest the Chinese government’s actions and the environmental devastation plaguing the country. However, weeks after the first exchange of messages, taking turns between different encrypted platforms to avoid any spying interference from Chinese entities and authorities, as has already occurred through Chinese apps such as TikTok27, Howey Ou, now living out of China due to the constant threats she was subjected to, for no apparent reason, has reverted to silence again.

Due to the importance of rare earths as a strategic sector for the Chinese economy, Raquel Vaz-Pinto says she is “not very optimistic about what is happening in these cities,” referring to the repression of anti-pollution demonstrations in areas affected by the extraction and refining of rare earths. She adds that the level of repression during the second mandate of Chinese President Xi Jinping has increased considerably, and is characterized by greater control and repression, both in terms of human rights and civil rights.

The autonomous regions of Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia are geopolitically and economically strategic regions for China due to the abundance of natural resources. They are, however, also regions of conflict due to ethnic reasons.

Fearing the proliferation of separatist movements for decades, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has implemented strategies aimed at ethnic homogenization, by gradually replacing the ethnic minorities of the autonomous regions with the Han majority, which today represents 90% of the Chinese population28 and the majority of the population of the three regions. The strategies used have been either through the use of trade routes, using the railway links not only to transport goods but the Han ethnic population29 itself, but also through an ethnic cultural cleansing, such as what is currently taking place in Inner Mongolia, or by implementing even more brutal strategies, as in the case of Xinjiang where genocide and crimes against humanity are taking place against the Uighurs and members of other ethnic and religious minorities, according to the U.S. Government’s 2021 report30 by the Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory of the U.S. Government.

The July 2020 study35 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Human Rights Initiative, on concentration camps in Xinjiang and the Uighur genocide explains that forced industrial labor is seen by the Central Government as the best method of assimilation of the Han culture for ethnic minorities. In the same study, the submission of ethnic minorities to forced labor programs is proven, and several Western companies have been identified as importing products originating from the forced labor of Uighurs, and one of the primary industries of this forced labor is the mining industry for extracting and refining rare earths (confirmed by the Human Rights Watch in 2020 and the Save Uighur project in 2021).

The non-profit organization WOIPFG36 published on July 20, 2019 a report entitled “The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Prison Slave Labor Industry – the CCP’s Secret Weapon in the Trade War.” The document reveals that the Chinese enterprises using Chinese prison slave labor are mostly state-owned, composing an aggressive economic and commercial strategy tactic to keep China at the forefront of international trade through low-cost production that the West cannot compete with.

These make up a centrally managed and unified prison enterprise system which is monitored and funded by, and exists under, the CCP’s judicial system.

The document substantiates the use of convict or forced labor by Inner Mongolia Hengzheng Group Baoanzhao Agriculture, Industry, and Trade Co., Ltd. also confirming that “Through its investigation, CBP has determined that there is sufficient evidence to support the finding that Baoanzhao is a prison/forced labor facility (…).”

According to Appendix 2.12 – “Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region”40 of the WOIPFG report, concerning state prisons that are forced labor facilities in Inner Mongolia, the mentioned company is listed in the document as a company owned by Baoanzhao prison located in Jalaid Banner (Hinggan League, Inner Mongolia), administered by the Department of Justice of the Prison Administration of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, which in turn is controlled by the CCP.

According to the data in the annex, this company is part of the state-owned Inner Mongolia Hengzheng Industrial Group Co., Ltd., an affiliate of the Department of Prison Administration of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, the Inner Mongolia government functional organization responsible for the province’s prisons, a group that owns 22 units of prison enterprises.

Documentation on existing Laogai41 by Chinese province by 199242, collected in the book Laogai, the Chinese Gulag, confirms that Baoanzhao prison was already part of the CCP’s (forced) labor reform system in 1992.

Appendix 2.12 of the WOIPFG report also indicates that the Baotou prison, a key detention facility in the Baotou municipality, the “rare earths capital”, is owned by Inner Mongolia Hengzheng Group Baotou Industry and Trade Co., Ltd., which is responsible for the production of electronic components, in which rare earths are crucial elements, and metal processing (among other products).

Appendix VI of the report “Continued Crackdown in Inner Mongolia,” entitled “Labor Camps, Prisons and Other Detention Facilities in Inner Mongolia” through 1992, confirms the existence of one such prison facility using forced labor, in the Bayan Obo mining district (name: Bayun E’bo Kuang Qu; located under the administration of Baotou County), dedicated to rare earths mining, confirming the use of forced labor in this industry.

The largest rare earth mining mine and industrial complex in the world (the Baogang Steelworks), owned by the “Baotou Iron and Steel Mill” group43, is located in the Bayan Obo mining district.

Appendix VI also indicates the existence of the Baotou Municipal Labor-Reeducation Center44, which provides workers for the Baotou Iron and Steel Mill, the state-owned company in charge of rare earth production in Bayan Obo.

According to Radio Free Asia, in February 2019 accounts by Chinese officials were made public confirming the transfer of ethnic minority Uighur prisoners from “reeducation camps” in Xinjiang. They were secretly taken to other locations and detention centers, such as Wutaqi and Salaqi prisons (both included in Appendix 2.12 of the WOIPFG report) in Inner Mongolia and Sischuan province (provinces where rare earths are extracted from), in order to hide the proportions of the Xinjiang genocide from the public and international scrutiny – a relocation process that was reportedly initiated in October 2018, says RFA’s Uighur Service.

These days, in the midst of the Green Revolution, there is a great deal of concern about green conflict minerals, which encompass the fuels needed to transition to a low-carbon economy – such as rare earth metals.

In countries where there is political instability regarding the governance of the mining sector, through abuses of state power or illegal activities, the extraction of these minerals may be linked to violence, conflict and human rights abuses.

In fact, according to data from the IISD report, rare earth mines in China have been considered “sites of exploitation” with incidents linked to the use of child labor, exposure of workers to high levels of toxic substances, and hazardous working conditions (Schlanger, 2017).

This reality is particularly worrying in the case of illegal mines (in abundance in Jiangxi province), which supply black markets, engaging in severe human rights abuses as they are not under any legislation, threatening the safety of workers and local communities (according to the New York Times in 2010 and Quartz in 2017).

The OECD approved the “Due Diligence for Responsible Supply Chains in Minerals Sourced from Conflict or High-Risk Areas” guide in 2010 to ensure transparency and ethical accountability of value chains. However, since China is not part of the OECD, it has no duty to comply with these directives, nor to share information about what happens along rare earth value chains.

In the face of European efforts to guarantee sustainable but also responsible development, Raquel Vaz-Pinto asserts: “the European Union has made a very big effort, unlike other parts of the world, but it is not enough by any means. We need to do more and better about the whole process, whether in environmental matters or in human rights”.

Given this scenario, it is necessary to trace rare earth value chains in order to prevent greenwashing processes and complicity with human rights abuses.

However, the tracing process is a complex one due to the diversity of stages in the value chain of ores, making it difficult to ensure that companies are truly transparent and green, as well as to control undeclared minerals that are introduced to the international market through smugglers, Guillaume Pitron points out in The Rare Metals War. The case is even worse when the major supplier is China, since there is an immense difficulty in obtaining official data from the Chinese government, Ana-Maria Martinez points out.

Vítor Correia, the secretary-general of the International Raw Materials Observatory (INTRAW), declares that, given the growing demand for ores, “we need a transcontinental agreement, not just a European one, because there is no country in the world that has all the raw materials its industry needs. Not even China. However, he adds that international cooperation is undermined by the growing nationalism with which each country seeks to solve resource management problems.

Julian Hilton goes on to say that if “we go down the path of resource nationalism, we will face terrible problems in terms of conflict and weaponization of results”, so the way forward must be through international cooperation and holding accountable those who should be held accountable, applying a series of tools that make it possible to trace value chains, and that aim to guarantee the right and duty, not only to Western consumers, but to the entire world population, to strengthen the guarantee for sustainable and ethical value chains, by fighting against the conflicts that arise from the exploitation of minerals – tools such as Blockchain technologies, which are currently being developed by UN working groups.

The current energy transition based on rare metals has had repercussions at the geopolitical level, with the restructuring of political and commercial partnerships with oil exporting countries, such as the United States with the Persian Gulf countries. In the case of the European Union, less dependence on Russia, Qatar and Saudi Arabia for fossil fuel imports would mean an increase in the energy sovereignty of its member states.

The report “Rare Earth Magnets and Motors: A European Call for Action”, created in 2021 by ERMA and ERMA’s Rare Earth Magnets and Motors Cluster, in partnership with the European Union and EIT Raw Materials, reflects on the serious environmental problem, which is evident in the way rare earth mining is carried out in China, underlining Europe’s potential as a world leader for a sustainable production of rare earth materials, the major goal of this “European Call for Action” being to turn Europe into a world leader in the supply of rare earths and rare earth magnets.

One of the solutions that has been found is the implementation of the circular economy47 concept to the production of rare earths through waste management and the creation of a market for secondary raw materials, in this case rare earths, focusing on the recovery of rare earths from secondary sources.

According to the “European Call for Action”, these measures include the need to ensure that end-of-life products, i.e. electronic waste containing rare earths, do not leave Europe, by introducing regulations and standards that facilitate the reprocessing and recycling of these products.

Guillaume Pitron, in The Rare Metals War, faced with the implementation of rare earth recycling techniques, offers a glimpse of the future: “a world in which the mining powerhouses are not the countries with the richest mineral deposits, but those with the most abundant waste dumps”, pointing to the geopolitical reorganization, according not to the value chains of minerals, but to their recycling.

ERMA’s key work involves addressing this European dependence on the Chinese supply chain by identifying a number of projects in the European Union that cover the supply needs of rare earths, either through domestic supply or recycling. ERMA has identified 14 projects that could lay the foundation for the European rare earths industry, capable of covering 20% of the demand for rare earths by 2030. The projects, which have been awarded European investments, are linked to the promotion of the circular economy, namely through the recovery and recycling of rare earths from different secondary sources, such as electronic waste, and using different techniques, such as urban mining48 – “a kind of fantastic solution, because while dealing with waste it finds the raw materials that are needed,” says Vítor Correia.

REE4EU is one of those projects. It is funded by the European Union and it is dedicated to the recovery of rare earth magnets from end-of-life products, considered by the European Commission, as the most advanced rare earth recycling project in the European Union, according to the Joint Research Centre’s 2020 report49.

REE4EU offers a technological alternative from European sources for companies to obtain rare earths from recycled waste, ensuring that their value chain is sustainable and ethical.

Unlike many other projects, this one manages to close the full cycle of recycling permanent magnets, without generating waste, as they use the waste material in the production of a new product, and are able to produce magnets from the recycled materials with exactly the same properties as the initial products. “Our environmental footprint is very good and our technology is competitive compared to Chinese prices, so we were awarded the Solar Impulse Foundation’s efficient solution award,” says Ana-Maria Martinez.

Another high-profile project in the field that is funded by the European Union is SecREEts, which focuses on the reuse of rare earths from industrial materials from the fertilizer industry. Their goal is to develop and ensure the entire value chain of neodymium permanent magnets in Europe without having to resort to mining, Clara Boissenin explains.

In addition, N9VE, a Portugal-based project, develops algae-related technology to separate, concentrate and recover critical technological elements, especially rare earths, with environmental sustainability as a major guide for operations, according to José Pinheiro-Torres, the founder and CEO of start-up N9VE.

Numerous projects directly or indirectly related to rare earth recycling have been founded in the European Union. Several projects have already been completed, some culminated in patents, companies or have been subject to other investment opportunities50.

Despite the potential of rare earth recycling projects, the technologies of many of these projects are not yet economically viable, nor are they scalable to industrial levels in order to compete with the Chinese market, claims the IISD 2018 report on “Green Conflict Minerals”.

Several researchers who were interviewed linked to rare earths recovery and recycling projects also mention that citizens and industries take a long time to dispose of their electronic waste for recycling, delaying the recycling process, thus creating obstacles to the sustainability of the rare earths industry in the European Union (according to EURACTIV in 2019).

Regarding operational obstacles, José Pinheiro-Torres refers to the slow bureaucratic pace as an impediment to the rapid development of projects, and the idealism of the EGD, which presents a series of measures, ideals and values that “raise the spirit”, lacking the materialization of the plan through investments and tangible measures. Maria da Graça Carvalho stated the same to newspaper Público, in 2021, referring that the EGD’s greatest challenge is not in the document itself, “Europe never had any trouble outlining good strategies. Where it sometimes falls short of expectations is in its implementation.”

As the mines on European territory have progressively closed over the last decades, Europe has gone from producing about 60% of the world’s heavy metals in 1850, to 3% according to ICMM51.

Given the exponential demand for rare metals, and the present and future needs for rare earths, and considering the European Union’s current supply capacity, it is necessary to rethink the sources of rare earths supply, since the European Union cannot just survive on the market for rare earth secondary raw materials without digging mines, explains Ana-Maria Martinez.

According to the “European Call for Action” for rare earth magnets and motors, Europe holds significant reserves of rare earths, but suffers from a lack of mining infrastructure, as mines are not operational and the average start-up time for a commercial mining project is 16 years52.

Regarding the fear of pollution inherent to the mining industry, mining techniques have undergone major advances in recent decades, allowing the mitigation of “environmental impact”, according to António Mateus, a Geologist at the Faculty of Science, University of Lisbon53. The “European Call for Action” itself explains how the increased use of renewable energy in mining and refining of rare earths could significantly reduce the environmental impact of extracting primary raw materials.

However, the lack of information or the misinformation regarding the modernization of mining techniques and what it entails to open a mine generates negative reactions and acceptance problems for civil society, especially when it comes to opening mines near their places of residence.

The Greenland Project in Kvanefjeld, Greenland – “the European Union’s hope for rare earth mining,” notes Ana-Maria Martinez – was the largest rare earth mine project in Europe, but was cancelled by government decision due to social discontent and public pressure (Reuters, 2021).

Clara Boissenin, who works in the field of social acceptance of rare earths, explains the importance of explaining to citizens the need for opening mines and what it implies not to do that on European territory. “The relocation of dirty industries has helped keep Western consumers in the dark about the environmental costs of our way of life,” says Guillaume Pitron, appealing to the urgency of the West, and in this case the European Union, to take on the production costs associated with the rare earths industry, since producing in Europe under high environmental and social standards would mitigate the damage caused by China’s rare earths industry.

MEP Lídia Pereira, with whom we spoke a few days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, mentions the importance of rethinking the energy mix and restructuring energy sources at a European level, calling for the need, for example, for France to open up to Portuguese renewable energy consumption, given also the difficulty of storing renewable energy and the need to export surplus energy.

In light of recent events worldwide, given the sanctions imposed by several countries on Russia, particularly regarding energy imports of oil, natural gas and coal, this rethinking of the structure of energy supply in Europe becomes an even more relevant issue, since several European countries are highly dependent on Russian energy sources, thus demonstrating the need to diversify energy sources in order to ensure energy subsistence in the current global climate.

“The sanctions we have imposed on Russia, as we have seen, involve costs for countries and families, such as the case of natural gas, whose prices have skyrocketed, which reveals the bad choices Europe has made in terms of energy policy management over the years,” says Lídia Pereira.

Yet the inclusion of nuclear energy in the European energy mix is still greeted with great doubt, being one of the main obstacles to its widespread acceptance the handling of the radioactive waste.

Carlos Santos Silva explains how Europe has been investing in the development of nuclear fusion energy for more or less 30 years, indicating that, in order to “reach the goals of zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, we’re going to have to go through nuclear energy, otherwise the transition is not sustainable and we won’t be able to reach the goals.”

According to Vítor Correia, for the energy transition to be viable, two conditions are necessary: “an energy mix that doesn’t exclude anything and a consumer-centered approach, in which everyone is willing to reduce their consumer metabolism.”

In fact, the sustainability of a product does not come for free, and as seen, the extraction and processing of rare earths produces an environmental footprint, and European consumers should and can be in a position to make informed purchasing decisions through tools that help them ensure the transparency of value chains and compliance with environmental and social standards. Those tools are being developed (according to the European Call for Action).

Vítor Correia, who argues that consumers are the best army against the climate crisis, human rights abuses and environmental attacks inherent to certain practices of exploitation of our planet’s resources, explains the reasoning behind his thesis: the consumer’s purchasing choice or boycott have the power to redirect markets and their practices.

“Telling people that we are going to suffer the effects of climate change, because in these countries the extraction is not done in the best way, and we are the ones who buy the products they extract, which means they are extracting them for us,” can help change people’s behavior, Vítor Correia observes.

Francisco Veiga Simão, a researcher connected to the Circular Economy field and co-founder of the Energy and Climate Forum, calls for the importance of investing not only in Circular Economy, but also in circular thinking: “moving from the economic concept of circular economy to circular thinking and circular action, as individuals within a society”.

The implementation of this concept can be found in a sentence by Lavoisier: “In nature, nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed” – “this is what we have to apply to our own lives”, he says. During our conversation, Clara Boissenin points out the need to consume less: “for me, the main lever is to reduce our needs for these elements (rare earths), either by replacing them with other minerals – which is not always possible – or by reducing our energy consumption”. Carlos Santos Silva takes the current situation in another way: “if we don’t rethink and lower our consumption level, we are going to lose this energy transition war. The planet can’t take it.”

When asked about the risk and criticality of rare earths, Julian Hilton ends the interview by saying, “the concept of criticality is highly dependent on your critical needs,” so at this point in time, given the global panorama, “the most critical of materials are our brains.” We are, therefore, at a time when we have to make choices, choices that fit in a trouser or coat pocket, choices that have an impact on the fate of specific individuals, choices that have an impact on our common home – planet Earth – in our tangible lives, and in the present and future History of Humanity.

Inner Mongolia and Ethnic Cleansing

Chinese and Mongolians, including those in Inner Mongolia, have different perceptions of History. According to a PhD thesis entitled “Ethnic Nationalist Challenge To The Multi-Ethnic State: Inner Mongolia and China” (2000), the modern Chinese nation can be seen as an entity constructed on the foundation of certain historical and cultural roots, invented or manipulated, involving the interpretation of historical facts, national heroes, ethnic relations throughout History, and the invention of traditions in order to create evidence that proves a sense of common Chinese unity and identity, homogenizing cultural and ethnic differences. Through this construction, the concept of the Chinese nation (Zhonghua minzu) is forged, thus creating a “rational” mechanism to unite efforts for economic development where there is no room for the notion of social progress, culminating in the elimination of all ethnicities and national differences (obstacles to economic progress), imposing a single identity – the Han. For Beijing, “unity and economic progress are much more of a priority than democratic principles,” Tim Marshall31 says.

Like Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia is also a geopolitically strategic area for the Chinese economy, as it holds 45% of the world’s supply of rare earths (in 2019, according to the report on Bayan Obo in EJA).

The 1992 report “Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia” by the Human Rights Watch/Asia reports on the campaign of repression and persecution, which the Chinese Central Government32 initiated in May 1991, against Mongolian ethnic groups in Inner Mongolia, including intellectuals linked to movements for the regeneration of Mongolian identity and culture, which had over the decades been devastated, and political dissidents, particularly against pro-democracy citizens.

Document No. 13, a confidential CCP document made available within the Human Rights Watch/Asia report, confirms the directives for the campaign of repression in Inner Mongolia, presenting lists of organizations deemed illegal and individual CCP targets, catalogued as “radical politicians,” individual testimonies included in the report confirm.

The 1992 pattern seems to be repeating itself today: “we have been observing very strong signs of a greater level of control by Beijing in Inner Mongolia,” explains Raquel Vaz-Pinto.

On September 3, 2020, a law was enacted in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region to replace the teaching in the local language, Mongolian, of three core subjects in schools by Mandarin (The Observers, 2021).

In September 2021, the Inner Mongolia Ministry of Education announced the implementation of new, stricter rules, with the removal of Mongolian history and culture textbooks from primary and secondary schools, according to the South China Morning Post.

Critics of this policy see it as “the latest move in a decades’ long campaign aimed at erasing the Mongolian culture.” (in Intellinews, 2021)

The new laws have triggered long-standing fears of ethnic suppression and large demonstrations in several Inner Mongolian cities – the largest ethnic Mongol protest movement in the last decade, according to the Financial Times –, which have been met with heavy repression by authorities and threats by the government, as stated by the Los Angeles Times in 2020.

The Chinese Central Government has increased repression in Inner Mongolia, using now-familiar tactics against ethnic minorities in the face of the threat to “social stability,” such as surveillance of suspects, financial threats and layoffs, arrests, blacklisting of individuals for social credit, control of the media, as one eyewitness who attended a protest in Xilingol, Inner Mongolia, tells the Los Angeles Times (also according to The Economic Times in 2020).

The fear of cultural suppression has generated a common perception among the people of Inner Mongolia: “We might be the next Uighurs,” claims Engehebatu Togochog, the President of the Southern Mongolia33 Center for Human Rights, based in New York (in The Observers, 2021).

Mongolian activists claim to have no knowledge of concentration camps or mass imprisonment, but are witness to strong signs of forced assimilation, such as the marginalization of the Mongolian language, the destruction of cultural symbols and monuments, and the introduction of patriotism classes in which students have to prove that they accept Chinese nationality and culture and the ideology of the Communist party (according to The Observers, in 2021).

Having managed to obtain a document that covers the content taught in these “patriotism classes”, one can find several statements by Xi Jinping about Xinjiang as an example not to follow if the citizens of Inner Mongolia do not want the same fate, “making it clear that, in theory, we could be the next Uighurs”, says Engehebatu Togochog.

Regarding the restriction of freedom of speech and spread of information, which has led to the blocking of several Inner Mongolia communication channels, the constant propaganda of Chinese national culture, in cartoons, advertisements, all in Mandarin, threatens the next generation’s total loss of relationship with Mongolian culture, says Togochog.

According to a news article published in April 2020 on Bitter Winter, a media channel dedicated to human rights and religious freedom, as protests were multiplying over school reforms in Inner Mongolia, the CCP launched the “Xie Jiao Propaganda Prevention Month” campaign, claiming that religious groups banned in China were threatening the stability of the region. According to Bitter Winter, these campaigns against Xie Jiao, a term used to categorize religious movements banned in China, such as Falun Gong, have been used by the CCP over decades as justification to exercise control and repression.

The official U.S. Government document from the Congressional-Executive Commission on China entitled “Public Perspectives on Human Rights Practices in China” from 2002 reports that Falun Gong practitioners were subjected to the utmost atrocities, actively incited by the CCP and its leaders, in order to eliminate the Falun Gong belief, including sexual abuse of women; torture for weeks (sometimes leading to death); imprisonment of detainees in cages smaller than the individuals’ bodies; exposure of inmates, without clothing, to freezing temperatures outside; and repeated sessions of physical abuse.

Following Oyunbilig’s testimony, he states that for half a century the Mongols of Inner Mongolia have suffered the mass killing of innocent citizens, the destruction of religious establishments and forced cultural assimilation that has brought Mongolian culture and tradition to the brink of extinction, as well as the destruction of grasslands to exploit the region’s mineral resources for the interest of the Chinese Central Government.

As such, the pattern of repression that dominated Inner Mongolia in 1992 and 2002 appears to be ongoing today, just as the repressive panorama currently operating in Inner Mongolia appears to follow a similar pattern to Xinjiang with regard to ethnic politics, as Adrian Zenz, the director and senior fellow in China Studies at the Memorial Foundation for Victims of Communism, briefly confirms to us via Twitter, having been playing a leading role in the analysis of leaked Chinese government documents on the case of Beijing’s concentration camp campaign in Xinjiang.

“There is no doubt in my mind that this greater control is also related to the location of those rare earths, meaning greater control and a greater desire that there is no sand in the gears that might endanger this value chain,” says Raquel Vaz-Pinto, who says she views the evolution of the Inner Mongolia situation with great pessimism.

In fact, in the US government’s Xinjiang Production Chain Business Advisory report34, published in 2021, the following statement is written on a footnote: “The U.S. government is also aware of reports documenting the expansion of internment camps to Tibet and Inner Mongolia to arbitrarily detain other ethnic and religious minorities and documenting the use of forced labor beyond Xinjiang (…).”